The 5 Worst World Chess Championship Games Of All Time

The 2021 World Chess Championship between GM Magnus Carlsen and GM Ian Nepomniachtchi is fast approaching. It takes a lot of talent, work, and dedication to play for the world championship. These players are always the best of the best, whether they win the title or not.

But they're still human, which has meant some poorly played games throughout the years, by both champions and challengers, players who won the match or lost it. Here are five of the worst World Chess Championship games ever played:

- Game 23, Mikhail Chigorin vs. Wilhelm Steinitz, 1892

- Game 14, Emanuel Lasker vs. Frank Marshall, 1907

- Game 1, Emanuel Lasker vs. David Janowsky, 1910

- Game 16, Alexander Alekhine vs. Max Euwe, 1937

- Game 1, Boris Spassky vs. Bobby Fischer, 1972

- Conclusion

Game 23, Mikhail Chigorin vs. Wilhelm Steinitz, 1892

Wilhelm Steinitz became the first official world champion in 1886 and successfully defended his title three times, including twice against the Russian master Mikhail Chigorin. Steinitz won their first match in 1889 relatively easily, but the second was much closer.

In 1892, Steinitz and Chigorin were tied at eight wins apiece after 21 games, with the first to win 10 games winning the match. In the 22nd game, Chigorin erred in the opening and lost. But that was nothing compared to the 23rd game.

Despite playing the super-aggressive King's Gambit, Chigorin invited a queen trade on move 11, completely nerfing his attacking chances. But Steinitz slowly let his advantage melt away, leaving Chigorin a piece ahead and significantly better by move 31. Chigorin was about to even the match at nine wins each!

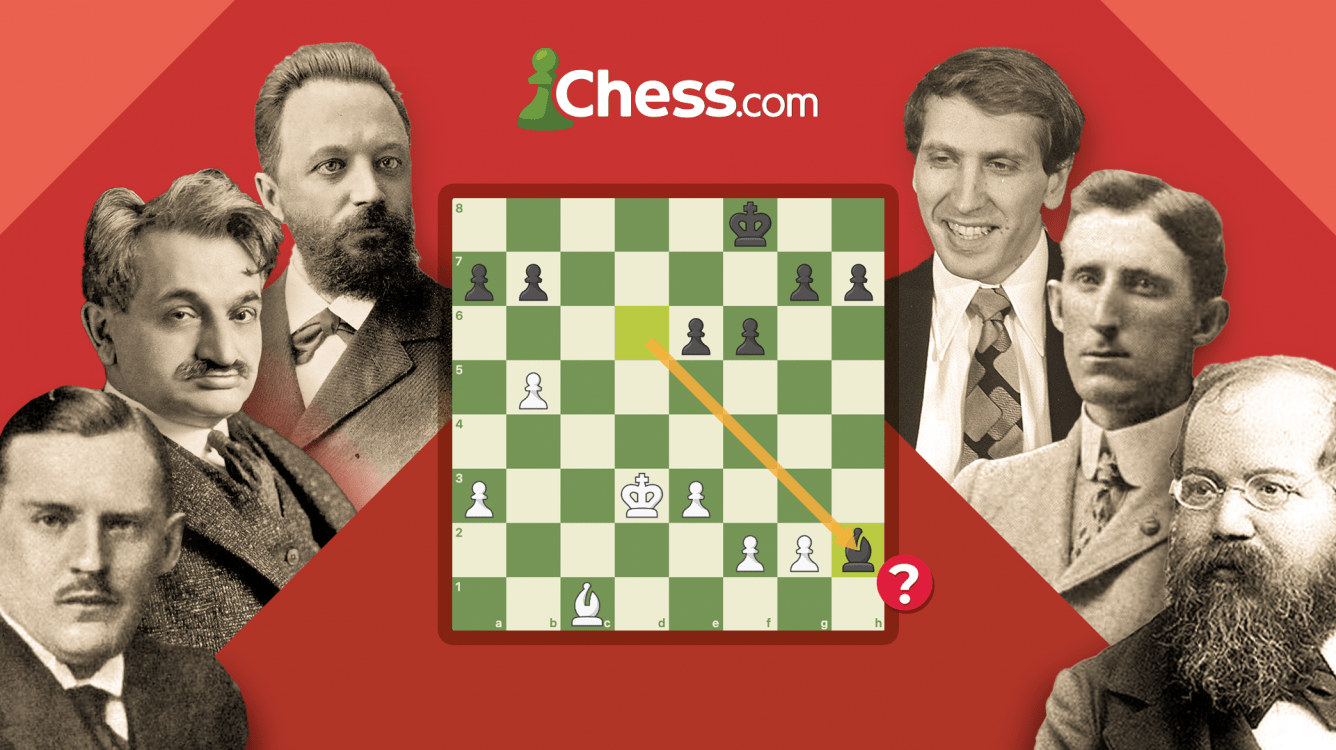

A single move later, Chigorin had lost the game, the match, and the last chance he ever got at the world championship; the brutal 32.Bb4?? abandoned the h2 square and allowed a mate in two moves. Two years later, Steinitz would give up his crown to Emanuel Lasker.

Game 14, Emanuel Lasker vs. Frank Marshall, 1907

Six of Lasker's seven matches for the world championship were not particularly competitive, with the winner scoring at least four more wins than the loser. Lasker's 1907 match against Frank Marshall was his first defense in 11 years, and it was one of the most lopsided: eight wins for Lasker, seven draws, and a grand total of zero wins for the American master Marshall.

After 13 games, Marshall was down 6-0 and getting desperate, or at least desperation is one of the more logical explanations for the rather ridiculous sacrifice 11...Bxh2+??.

The "Greek Gift" is a common chess theme, but the player making the sacrifice usually has more than one piece developed. Pro tip: If ...Ng4+ just hangs the knight and ...Qh4+ isn't possible, don't waste your time even thinking about playing ...Bxh2+. An attacking master like Marshall had no chance either.

On top of that, everyone recognizes the importance of piece activity and development, yet Marshall did not touch a piece on his queenside until move 17. Four moves later, he resigned.

Some miniatures feature brilliant attacks, and some... do not. Marshall lost the next game as well, and his championship efforts were over.

Game 1, Emanuel Lasker vs. David Janowsky, 1910

In his match vs. David Janowsky, Lasker somehow won even more easily than against Marshall, again 8-0 but this time with just three draws. And Janowsky's troubles started right in game one.

An aggressive player, Janowsky played Siegbert Tarrasch's defense to the Queen's Gambit (3...c5), where Black accepts an isolated d-pawn in exchange for piece activity. After 16 moves, however, Janowsky ended up with two isolated pawns on the queenside. Facing a difficult defensive task in the heavy piece endgame, Janowsky tried to shore up the position with the blunderous 19...Rd6??

This move simply loses a piece, in a tactic that appeared on the board prior to Janowsky throwing in the towel.

Janowsky managed to draw the second and third games of the match before getting wiped out with just half a point in the next eight contests. Although game one would remain his worst effort of the duel with Lasker, it had set the tone for the most lopsided world championship match in chess history.

Game 16, Alexander Alekhine vs. Max Euwe, 1937

In perhaps the greatest upset in world championship history, Max Euwe defeated Alexander Alekhine in 1935, but Alekhine was on his way to regaining the title when this game happened.

To understand why it is so bad, we turn to GM Andrew Soltis' 1994 book, The Inner Game of Chess: "If this position [beginning with White's 26th move] appeared in a magazine under the heading 'White to play and win,' most amateur tournament players would be able to find 26.Qh8+!. Certainly, 99 out of 100 masters would find this elementary queen fork." Here we start the game a move earlier for context.

Not only did Euwe's 25...Qe5 allow 26.Qh8+, and not only did Alekhine miss it, but then Euwe missed it... again. In fact, Qh8+ on move 27 was going to be even better for Alekhine, and yet the move still again went unplayed. Euwe finally protected his queen with 27...Bd6 to end the shenanigans, but the two world champions had gone two moves each without seeing the two-move forking combination. "And," as Soltis continues, "the game drifted to a 65-move draw."

Their blindness is our gain, however, as observing these themes from a distance helps us recognize such opportunities when they arise in our own games. Perhaps GM Tigran V. Petrosian was aware of this game and its Qh8+/Nxf7+ motif when, nearly 30 years later, during one of the best games in world championship history, he played this stunning final combination.

Fortunately for both Alekhine and Euwe, their 16th game ultimately had little effect on the outcome of the match, which Alekhine won easily, by a margin of six games.

Game 1, Boris Spassky vs. Bobby Fischer, 1972

Earlier we saw one challenger, Janowsky, play very badly in his championship debut. But no less a chess superstar than GM Bobby Fischer played a very odd first game as well.

The most famous chess match in the history of the world should have begun with a draw. Short of removing all the pawns, it's hard to even imagine a more drawish position than this game has at move 29.

That changed with 29...Bxh2? There was zero chance of this move actually winning a pawn without losing the bishop, and the game slipped away from Fischer. So why did Fischer play the move? Hallucination? Arrogance? Boredom?

We'll never really know. But in Pawn Sacrifice, the 2014 dramatic adaptation of the 1972 match, Spassky (played by Liev Schreiber) had an idea: "A man who is prepared to commit suicide always has the initiative."

Fischer managed to find an even more suicidal way of losing the second game: by forfeit. He didn't even show up for the second game and was staring at a 0-2 start to the match. Of course, Fischer was no Janowsky, and recovered from a bad game one (and non-existent game two) to win this match. No harm, no foul.

Conclusion

The more chess that happens, the better it gets. That is true on the individual level: play more, study more, see more patterns, get better. It is also true on the macro scale. Only one of these games happened in the last 80 years, and none in the supercomputer era. There certainly continue to be bad games among top players, some of which could even have made it into this article, but chess is better now than ever, and there have never been more resources for the aspiring player.

And if players of the caliber of an Alekhine or Fischer are capable of rotten games, it should make us feel less bad about our own errors at the chessboard, and give us the confidence to forge ahead.