Even more adventures with endgame tablebases

Endgame tablebases are remarkable software that effectively plays perfect chess in any position with up to seven pieces. As such they are an invaluable analytical tool and in two previous blogs (Adventures and More Adventures), I demonstrated some of their capabilities. Besides analysing existing endgames, tablebases could also assist in the creation of new positions with intriguing and even study-like play, and last time we looked at two examples of mutual zugzwang (MZ) extracted from the Syzygy tablebases. For this final part of the series, I have picked three more special cases of these paradoxical situations, again from the massive MZ files produced by Árpád Rusz. The first instance lends itself to conversion to an actual endgame study with some neat and precise variations. The other two settings are almost unbelievable in exemplifying double zugzwang, because in these positions both sides are able to promote a pawn safely, meaning each player would prefer it if the other side were to queen first!

In a mutual zugzwang position, each player would be worse off if given the turn, because every legal move of each side entails some exploitable weakness. The MZs presented here (unlike those in the last instalment) are not full-point ones but of the more standard type: if White is to move, Black would be able to draw, yet if Black is to move, White would have a forced win. In the analysis provided, unique drawing and winning moves, by Black and White respectively, are given with an exclamation mark. Further, the diagrams are accompanied by links to the Syzygy tablebases that will open with the positions already set up; hence you can easily follow the main variations on that site and also explore any lines not covered. Such Syzygy links have been added to the two earlier Adventures blogs as well.

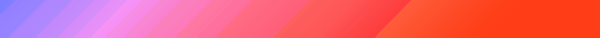

In the first diagram, White seems to have the advantage despite being a pawn down, because of the advanced a-pawn supported by the king. But an immediate attack with 1.Kb7? or 1.a7? only draws, largely due to the centred black king which has flexible defences. Black’s connected passed pawns are of course dangerous too and after, say, 1.Nf4? h4!, White even loses with any continuation except for the drawing 2.Kb7 or 2.a7. [Syzygy TB Link]

The correct opening 1.Nh4! places the knight in a less exposed spot and brings about the MZ position. Imagine if it’s White to move again [Syzygy TB Link], then surprisingly no win is possible: either 2.Kb7 Kc5! 3.Kxa8 (3.a7 Nb6) 3…Kb6! 4.a7 Kc7! or 2.a7 Ke5! 3.Kb7 Kd6! 4.Kxa8 Kc7! would trap the king and leave White unable to progress, as the knight is stuck holding off the black pawns. Or if White tries 2.Nf5+ then 2…Ke5! gains a vital tempo by threatening the knight, e.g. 3.Nh4 (3.Ng3? loses to 3…h4!) 3…g3 4.Kb7 Kf4! 5.Kxa8 Kg4! 6.Ng2 h4 7.Kb7 h3! draws.

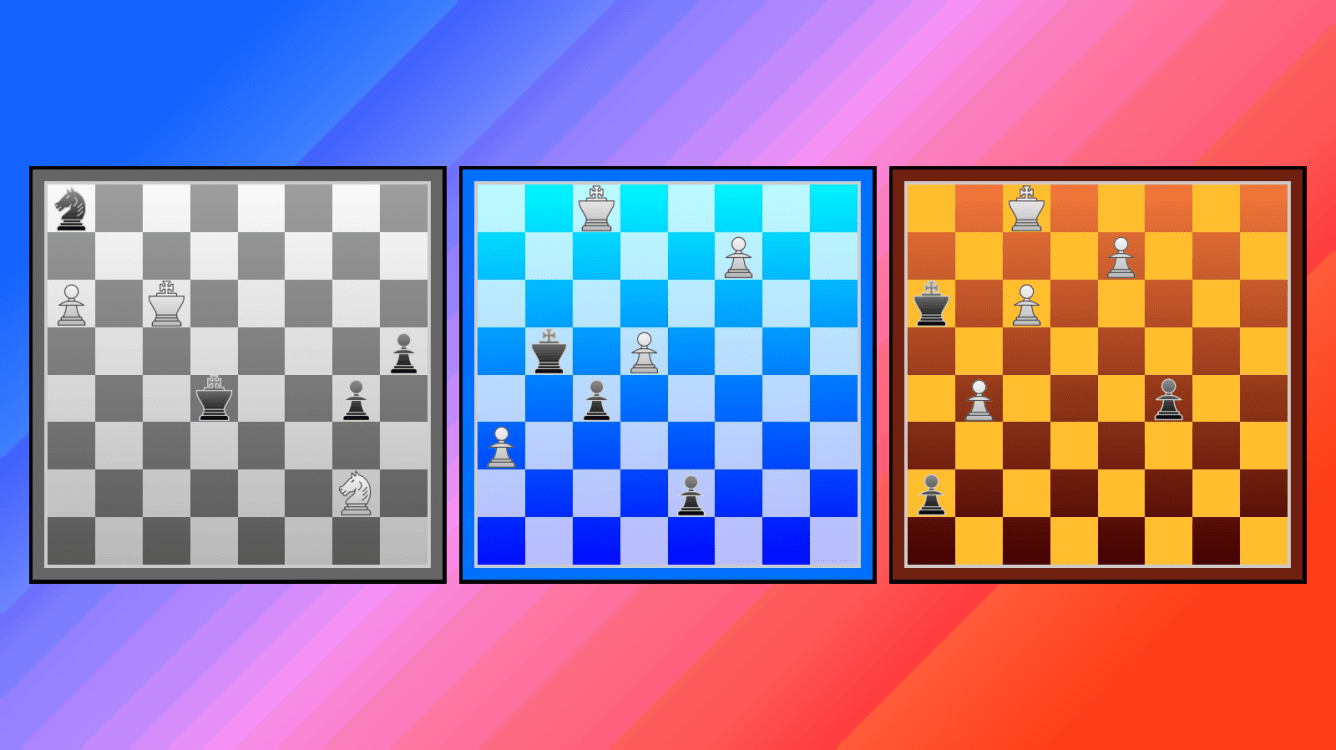

I will finish this three-part series with two complex positions that may not be fully comprehensible, but which are fascinatingly counter-intuitive. Each setting contains five passed pawns, most of which seem free to push forward. That includes two pawns of different colours that are ready to promote, and either could do so without fear of losing the new queen to any simple tactics. Yet the outcome for each side would be better if the other were to move and could promote first. These MZ situations thus represent a sort of antithesis to the pawn race!

What’s happening here is that when the two players promote in turn, that leads to another MZ in which both queens (as well as every other piece) would prefer to stay put. The queens are already ideally placed because they control various critical squares in different directions. Now whichever queen is compelled to move first, it cannot maintain its “focus” on all of these squares, and this loss of control is immediately punished by the other side. The numerous squares that must be covered by the queens, for both offensive and defensive purposes, account for the complexity of the play. Nonetheless, in the given variations we see general principles at work that are quite understandable for such queen and pawn endings. Black, who is a pawn down, typically aims for perpetual check and sometimes draws by winning one of the two white pawns. White’s chief weapon against perpetual check is to force a queen exchange that will leave a won pawn ending. However, the deciding factor in such a simplified pawn ending is not so much White’s extra material but how advanced the remaining pawns are, and if White is not careful, Black could even win with a better placed pawn.

In the first case below, after the two promotion moves, both queens are focusing on two key squares, e8 and b4. Either queen could give a strong check on e8 if it’s left unguarded, while the white queen has another check on b4 that’s prevented by the black promotee. Another important square is c5, defended by the white queen and black king against each other. [White to play - Syzygy TB Link] [Black to play - Syzygy TB Link]

The final position is even more intricate. After both sides have promoted, the white queen guards h8 and e5, two invading points for the black queen. The latter is ironically well-placed in the corner, because it further threatens checks from the a-file when the black king moves. For instance, suppose Black is to move and plays 2…Kb6 (threatening 3…Qa8+/Qa6+), White’s only winning reply is 3.Qd8+!, taking advantage of the check to gain a tempo. But that means d8 is another key square that the white queen has to keep focusing on. If White starts instead and chooses, say, 2.Qe2+, then d8 is no longer accessible and Black draws uniquely with 2…Kb6! [White to play - Syzygy TB Link] [Black to play - Syzygy TB Link]