The Greatest Chess Player Who Never Became World Champion?

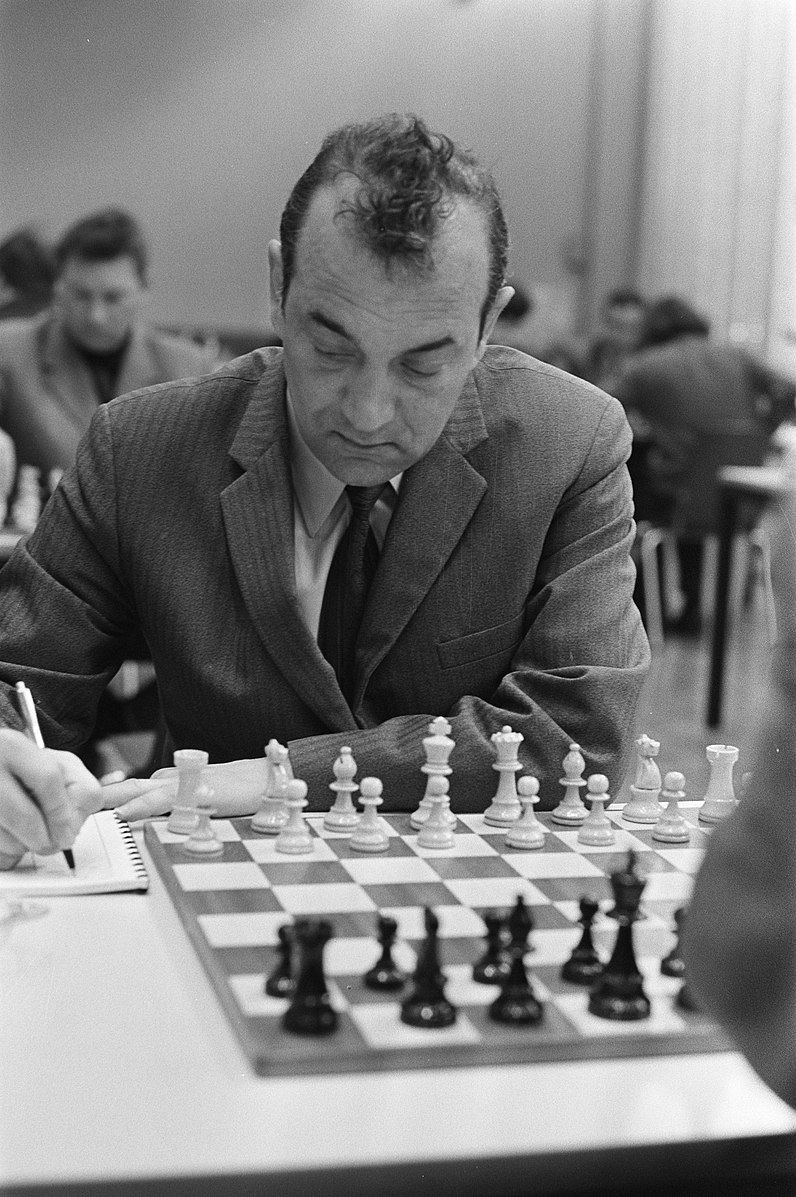

GM Paul Keres is undeniably one of the greatest players of all time, a renowned chess writer, and one of a handful of grandmasters inevitably discussed whenever we speak of that hallowed company that came ever so close to winning the coveted title of world champion.

During a 30-year period between the 1930s and 1960s, the Estonian grandmaster was one of the most dominant players in the world. Of those who got close to the throne but never wore the crown, Keres along with GM David Bronstein deserve the top distinction, in my view.

Only Bronstein, GM Victor Korchnoi, Akiba Rubinstein, and the equally star-crossed GM Leonid Stein were close to Keres in consistency of excellence as well as match and tournament results.

It was during this 30-year period that Keres won the prestigious AVRO tournament of 1938, the last significant tournament before WWII which put him directly in line for a title opportunity against the legendary icon Alexander Alekhine. Unfortunately, the war interrupted the plans for the title match and Alekhine died shortly after; however, Keres qualified for the Candidates Tournament four more times in his career. He narrowly missed a chance at the world title five times!

Keres defeated nine undisputed world champions: Jose Capablanca, Alekhine, GM Max Euwe, GM Mikhail Botvinnik, GM Vassily Smyslov, GM Mikhail Tal, GM Tigran Petrosian, and GM Bobby Fischer. In addition, one of Keres' most popular books which was co-written with GM Alexander Kotov, The Art Of The Middlegame, continues to instruct and inspire nearly half a century after its publication.

- Playing Style And Place In History

- Estonian Champion To 1938 AVRO Tournament

- World War II And Match With Euwe

- 1948 World Championship And Beyond

Playing Style And Place In History

Paul Keres' style of play was bold yet balanced with an additional positional understanding and endgame finesse that many, if not most, other swashbuckling players lacked. In my opinion, only Alekhine and GM Boris Spassky equaled Keres in this degree of balance in their respective skills.

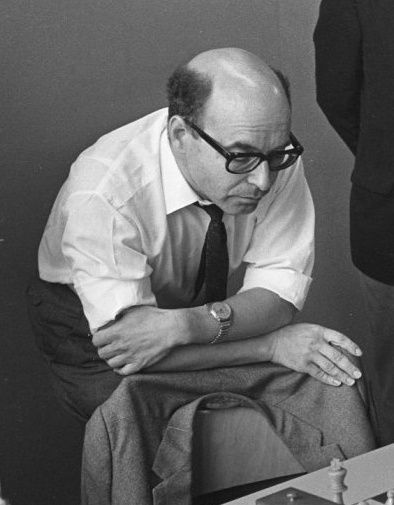

For instance, Bronstein was equally gifted when it came to combinational ability but lacked the endgame precision Keres possessed. It was none other than Botvinnik himself who said that if Bronstein had better endgame skills that he would have won their match for the world championship.

To me, Keres is the greatest player who never became world champion—especially when considering achievements, tournament results, career longevity, and overall consistency. The other players that come to mind are Korchnoi, Rubenstein, Stein, and Bronstein.

Bronstein and Korchnoi have the greatest argument after Keres, in my opinion, as Stein and Rubenstein just didn't have the same consistency over time for different reasons. In Stein's case, dying at the height of his powers from a heart attack, and in Rubenstein's case, leaving chess altogether for psychiatric reasons.

So this leaves Bronstein and Korchnoi. Bronstein has a better case than Korchnoi as their record reflects Bronstein having the edge 9-6 with 14 draws. I would also like to point out that Keres' individual record against Korchnoi speaks for itself and is reflected later in this article by none other than Korchnoi himself!

Don't get me wrong. I'm a huge fan of Korchnoi. When I was beginning to play in tournaments, Viktor was only 37 years old and ironically was yet to reach his peak that occurred a full decade later when he played the legendary world champion GM Anatoly Karpov in their famous matches. I believe that Keres was just a little bit better than Korchnoi, not to mention Viktor's own frank assessment below.

Ironically, in 1974 when Korchnoi was facing the final candidates match with Karpov, the sports committee and the leadership of the national chess federation were completely on the side of his opponent. This preference wasn't a secret among the Soviet grandmasters, and only Bronstein and Keres offered their services to Korchnoi. His reaction was remarkable.

He used Bronstein's opening ideas but gratefully turned down Keres' offer. His explanation after all of these years: "My score vs. Paul Petrovich was 0-4, and I had the feeling that if I agreed to his help, it would be Keres fighting at the board and not me.... His chess authority would have put too much pressure on me."

My score vs. Paul Petrovich was 0-4, and I had the feeling that if I agreed to his help, it would be Keres fighting at the board and not me.... His chess authority would have put too much pressure on me.

—Viktor Korchnoi

Much has been written of Keres' star-crossed life and rightfully so. "The Eternal Second" and "Paul The Second" are some of the monikers applied to Keres. His nemesis during many, if not most, of his prime years was Botvinnik, the grand patriarch of chess.

Estonian Champion To 1938 AVRO Tournament

In 1935, Keres tied for first place in the Estonian championship at age 18 and then won the subsequent playoff match to become the official champion. This win allowed him to represent his country in the Olympiad, Estonia's first-ever appearance in the hallowed chess event.

Keres played board one and finished with 12 out of 19 points. The success here impressed the international chess community a great deal and as a result 1936, 1937, and 1938 were very busy years for Keres.

Keres went to the 1937 Margate tournament for his first major international appearance. It also happens to be his first success against world-class opposition, and his achievement is epitomized by his victory over the world champion—the dynamic and mythical Alekhine, whom he defeated in just 23 moves.

Keres' play at this time is exemplified by bold and dynamic creativity, as his crushing victory over Alekhine indicates. In this game, Alekhine finds himself in trouble early in the game. Keres sacrifices a pawn on the 12th move and then Alekhine blunders on move 22, allowing Keres to deliver a memorable queen sacrifice:

Well, there is nothing like beating the storied Alekhine in one's first game against the legend in only 23 moves with a queen sacrifice. Can you, dear reader, think of a more auspicious manner to introduce yourself to the collective chess community? With this victory, Keres sent a message to the rest of the chess world. During this tournament, Keres tied with GM Reuben Fine for first place (and won the tiebreaks).

His success at Margate led to an invitation to the 1937 Semmering Tournament, which had a star-studded field that included Capablanca, GM Samuel Reshevsky, Fine, GM Salo Flohr, Eliskases, and Petrov. Keres stated: "I had no reason to believe I could compete with such players. I resigned to simply play good chess." It bears acknowledgment that Keres was only 22 years old at this point, and he finished a full point ahead of the illustrious field.

It was around this time that the newly created "Euwe Committee" (named after GM Max Euwe) together with FIDE organized a series of tournaments and established a candidates cycles where the winner would play Alekhine for the world championship. Until this time, going back to the days of Lasker, a talented challenger would have to present a challenge, secure financial backing, and then the champion could decide whether to play the challenger.

However, FIDE thankfully ruled against these antiquated and arbitrary criteria. In 1938 the famous AVRO tournament was held in order to establish a challenger for Alekhine. The players invited were Alekhine, Capablanca, Botvinnik, Smyslov, Keres, Euwe, Fine, Reshevsky, and Flohr.

Unfortunately, Capablanca (who had been battling problems with high blood pressure) suffered a mini-stroke in the second half of the tournament and finished in next to last place just above Flohr. Botvinnik's performance was noteworthy for beating both Alekhine and Capablanca—he finished third behind Fine and Keres, who both tied for first place with Keres winning the tiebreak. This is considered by most to be one of the strongest tournaments in the history of chess. It was an impressive performance, to say the least.

Keres was slated to face Alekhine for the world championship. The chess world was looking forward to what many were already calling a titanic match, but as I stated earlier, World War II broke out and that was that for a while.

World War II And Match With Euwe

The war broke out during the 1939 Olympiad and, as a result, many players left for home. But many teams stayed, and Estonia placed third. After the Olympiad, a notable number of players stayed in Argentina for the duration of the war, the famous Miguel Najdorf among them as well as the entire German team.

Keres stayed in Argentina for about a month after the Olympiad, finally returning to Europe in order to play a match with Euwe. It was to be a 14-game match in the Netherlands with the winner to play Alekhine. Euwe was by far the more experienced match player and had already faced Alekhine in two championship matches, winning and taking the title in the first match and losing the return match two years later.

However, it was only Keres' second match ever, though the poise he demonstrated belied his lack of match experience. The ninth game of the match with Euwe is often referred to as "Keres' Ninth" (a reference to Beethoven's Symphony No. 9) and is considered one of Keres' finest achievements in his fabled career.

Keres went on to win the match and had again earned the right to face Alekhine for the world championship, but his telling quote says it all: "So I won the match and thus secured a worthwhile victory on the road to the world championship, but in the meantime the possibilities of the match with Alekhine had sunk to a minimum as a result of the outbreak of the war."

So I won the match and thus secured a worthwhile victory on the road to the world championship, but in the meantime the possibilities of the match with Alekhine had sunk to a minimum as a result of the outbreak of the war.

—Paul Keres

The war years were terribly difficult for Estonia, which passed from Soviet control to German control and then back. After the war, Keres was allowed to participate in Soviet tournaments and promptly won the USSR championship of 1947.

Alekhine's passing in 1946 made way for a new era in chess. In 1948, the six best players were invited to participate in a tournament to decide who would become the next world champion. These included Keres, Botvinnik, Fine, Euwe, Smyslov, and Reshevsky (but Fine bowed out and was gone from chess not long afterward).

1948 World Championship And Beyond

During the 1948 World Championship tournament, the fate of chess in many ways was established, and this denotes the emergence of Botvinnik whose dominance would continue until 1963 when Petrosian finally dethroned him for good.

In this tournament, Keres had a great record against Smyslov and Euwe, less so against Reshevsky, and lost definitively against the champion Botvinnik, losing the first four games and not playing well at all against the patriarch until the outcome was no longer in doubt.

Many, including none other than Bronstein, have implied that Keres was pressured into "throwing" his games with Botvinnik. However, Keres was very complimentary of Botvinnik stating, "The champion played the best chess of all of us, and his result was well deserved."

In the 1950 Candidates Tournament, he did adequately but was disappointed in his results. At this time he was 34 but seemed to lack the sparkle that permeated his game up to this time. However, that year he won his second USSR championship and won again the following year.

In four consecutive candidate tournaments, Keres finished second, but his best chess for the most part is now behind him. At this juncture not only does he have to contend with Smyslov and Bronstein, but also emerging talents like GM Efim Geller and Korchnoi as well as Petrosian and Spassky, the latter two won the coveted title several years later.

However, it is noteworthy that from 1952 to 1964 Keres, playing board four for the Soviet Olympic team, managed to win the gold medal in every Olympics but one and the Soviet team won gold in all of these Olympics. After the 1964 Olympics, he was moved to a trainer position and did not play for them again until the "USSR vs. Rest of the World" in 1970, when he was on board 10.

Bronstein again claimed that Keres was told to lose to Smyslov during the 1953 Zurich Tournament, as Smyslov was now considered the favorite of the Soviet hierarchy. He won tournaments, however, in Hastings in 1957 and Mar Del Plata that same year. At Curacao in 1962, he finished second once more. In 1963 at the Piatorgorsky Cup, Keres tied for first with Petrosian.

In 1972 Keres finished at the top in Hamburg ahead of Petrosian, GM Wolfgang Unzicker, and, of all people, GM Lothar Schmid (the arbiter of the famous match between Fischer and Spassky).

One word used by all who knew him was "class." It's difficult to find a more loved and respected player from both a personal as well as a professional perspective. He was humble as well as low-key, two qualities that stand out both then and especially now in today's age of self-promotion and self-aggrandizement.

His last tournament win, fittingly in his native Estonia, was in 1975. He died later that year at the age of 59. To say he was well-liked and respected by all is an understatement. More than 100,000 people, over 10% of Estonia's population, attended his funeral.